This post is written for the #RealTimeChem week blog carnival, themed “New elements in chemistry” in celebration of the naming of elements 113, 115, 117 and 118.

At the time of writing, I’ve been back to research for two solid months, following an interruption to my studies due to Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS). I have previously written about my experience with this illness – a tale of woe that began over a year ago already. How time flies when you’re desperate not to waste a moment of your precious PhD scholarship!

I digress. In my previous post, I wrote about my experience with CFS and its impact on the quality of my life. It is one thing, however, to live with a chronic condition, and another entirely to return to research while still battling it. I’ve been steering clear of this blog out of the desire to conserve my energy reserves, but the #RealTimeChem week blog carnival theme is just too perfectly suited to my situation to ignore. “Are you adapting to a new life situation that’s affecting your chemistry?” asks the prompt. Yes! Yes I am!

There is a fundamental disconnect between the approach to chronic illness and to research. When doing research, your work and thoughts are rarely focused on the short-term, but instead looking into the future: at the big picture you will paint using your individual pieces of data. More practically, there are always more people who want to use an analytical instrument than there are time for in one day, so early sample preparation and pre-booking your time slot is important. On the other hand, the best-laid plans of mice and people with CFS often go awry. You can’t control when the illness raises its ugly head, so you can’t plan any days you might need to take off. You need to take things day by day, listening to the demands of your body. Moreover, as I talked about in my previous post, I have had a slew of neurological symptoms related to CFS that have tangibly impaired my ability to plan ahead. It’s an unfortunate double-whammy of short-sightedness. Thankfully, my supervisor has lost none of his foresight and from the moment of my return, suggested weekly meetings to discuss my progress. I take notes at these meetings so that plans or ideas we’ve had don’t go forgotten, even when my brain is at its worst. Additionally, I have taken to occasionally taking some time off simply to sit down, think about the experiments I’m running that day or week, and really ask myself why I’m doing them.

I do have days when I’m so confused about what I’m supposed to be doing and what I’m trying to achieve that I feel like bursting into helpless tears. Amusingly, it has become difficult to draw a line between “I’m doing research and I have no idea what I’m doing” and “my brain is foggy from CFS and I have no idea what I’m doing.” As the latter kind of confusion is alleviated by my recovery, the former grows; when CFS fogs up my mind, I don’t have the foresight to worry about the future of my project. In some ways, too, these new circumstances feel very familiar. This research-related helpless confusion is one I have felt, without fail, at the beginning of each research project in the past.

The second major limitation of chronic illness is also related to time, but in a more physical sense. As soon as I returned from sick leave, I successfully applied to change my candidature from full-time to part-time. Even so, I am only gradually becoming capable of meeting these reduced contact hours. In a positive aside, through sheer desensitisation, I’m learning to let go of the guilt that I used to feel on sick days. If I need to take a day off, I need to take a day off. Besides, guilt is an incredibly energy-consuming process, and I have come to accept that there is nothing to be achieved by maintaining it.

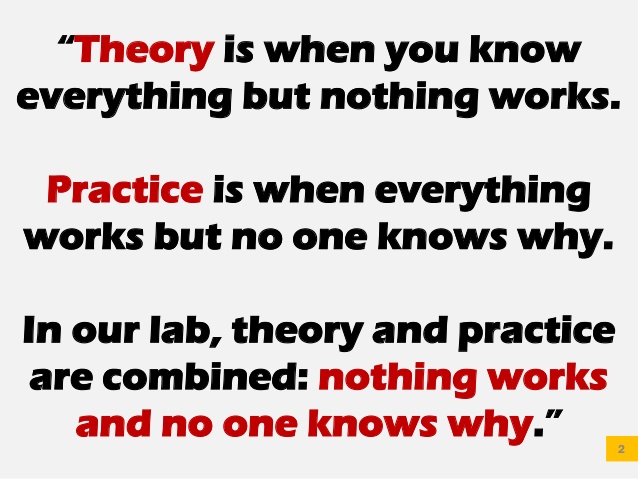

From my reduced working hours arises another ugly feeling that feels so much like deja-vu: frustration. Research chemistry is slow and labour-intensive. This is best summarised by words that aren’t mine:

Borrowed with love from slideshare.net/freerudite

This is, of course, an entirely universal experience in research. I’m simply feeling it more strongly now, perhaps, that I can feel weeks slipping by so quickly without much to show for them at all. The rate of trials has been reduced, so the errors simply feel more prevalent. This frustration is managed best by the company of my favourite coworkers, a glass of wine and sunny weekend days spent far from the lab.

On some days, I already feel like my old self: juggling obligations, pondering on ideas and constructing elaborate plans. I wake up tired, but it doesn’t feel like a life-sapping exhaustion, but more like a tiredness can be cured by some cups of coffee. I still regularly have to remind myself to slow down, because I’m prone to enthusiasm resulting in great bursts of effort that can burn through my energy reserves in a few measly hours. As a whole, I’m learning to manage my situation as it slowly, but surely improves.

At this point, I can cautiously permit myself this: I think I’m going to be alright.

As always, I thank the gorgeous community on Twitter for their support. If you haven’t found me yet, I tweet as @Lady_Beaker. I can also be reached via the comments, or by e-mail at chemistryintersection@gmail.com.